Fruitful Practices researchers Leith and Andrea Gray have stated that (63):

…church planting workers tend to view their mission strategy based on their view of what the church is.

So then, how should we form our view of the church?

Rebecca Lewis argues that pre-existing communities should become the church as she differentiates between planting the church and implanting the church (17):

Typically, when people “plant a church” they create a new social group. Individual believers, often strangers to one another, are gathered together into new fellowship groups. Church planters try to help these individual believers become like a family or a community…

By contrast, a church is “implanted” when the Gospel takes root within a pre-existing community and, like yeast, spreads within that community. No longer does a new group try to become like a family; instead, the God-given family or social group becomes the church.

Following this, the Grays say there are two models for church planting (63):

Some workers follow and attraction church planting model, in which the church is a new structure existing parallel to other social networks in the community. On the mission field, such workers share the gospel with various unrelated individuals and then gather them together into a “church” to which they gradually invite others from the surrounding community.

Other workers hold to a model of the church as the transformation of existing social networks. On the mission field, such workers share the gospel with a community of people who already know each other and that group gradually grows in knowledge of the Bible and obedience to Christ.

Where would someone form their view that the church is the transformation of a social network? This view would not come from Scripture. The church in the New Testament was made up of people who had nothing in common but the person of Jesus (of course there were some family conversions as well).

Instead, the “social network” model bases their views of the church primarily on their missiology, and their missiology primarily based off of observation. Rebecca Lewis (who has been instrumental in her work in insider movements) says (36):

My opinion is that missiology must be based on seeing what God seems to be doing and evaluating that in the light of scripture (copying the apostolic process in Acts 15).

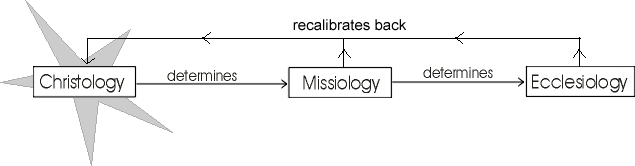

In this same vein, the Grays’ article was highly influenced by Frost and Hirsch, who argue in The Shaping of Things to Come that our Christology informs our missiology which informs our ecclesiology.

Simplistically, we can frame the issue as Jonathan Dodson does here (definitely you should read the comments to his post!):

Alan Hirsch advocates that Missiology should shape Ecclesiology.

Christology → Missiology → Ecclesiology

Ed Stetzer advocates that Ecclesiology should precede Missiology.

Christology → Ecclesiology → Missiology

Which do you support and why?

This issue of the primacy of ecclesiology or missiology is a foundational paradigm for how we think about the church and mission. Dodson follows up with this post:

…which should take priority in determining a missional ecclesiology—missiology or ecclesiology? Both Stetzer and Hirsch have kindly provided their schematics to help clarify their positions. Stetzer writes:

My point is that scripture sets the agenda and has provides direction for all three� one does not �come from� the other but they are all derived from scripture, interact with each other, etc

Ed Stetzer

Hirsch explains: We believe that Christology is the singularly most important factor in shaping our mission to the world and the forms of ecclesia and ministry that form that engagement…Before there is any consideration given to the particular aspects of ecclesiology, such as leadership, evangelism or worship, there ought to be a thoroughgoing attempt to reconnect the church with Jesus; that is, to ReJesus.

Alan Hirsch

Stetzer sets Scripture as the starting place and Hirsch begins with [the biblical] Jesus. What are the implications for these slightly different starting places? Do these differences matter?

It is precisely these differences that determine how we form our view of the church which then creates a difference between the two models of church mentioned above.

We must come back to Scripture to inform our Christology, missiology, and ecclesiology. And Scripture says the church is more than a transformed social network made up of people who look, talk, and think the same. Instead, the church is in fact a new social group where allegiance to Jesus and identity in Him is paramount to all other allegiances and identities. A simple look at the list of the scriptural metaphors for the church should remind us how diverse it is (Payne):

- Family (Matthew 12:48–49; 1 Timothy 5:1–2)

- Body (1 Corinthians 12:20; Ephesians 1:22–23)

- Priests (1 Peter 2:9)

- Fellowship (1 John 1:7)

- Community (Acts 2:44; 4:34)

- Temple (1 Corinthians 3:16)

- Building (Ephesians 2:19–21)

- Bride (Ephesians 5:22–33; Revelation 21:9)

- Branches (John 15:5)

- Sheep (John 10:1–18)

- Salt (Matthew 5:13)

- Light (Matthew 5:14)

IMHO, I think we should recognize that the social network model is a transitional form that can be helpful until we get to more robust, biblical forms of church. Until then we need to make sure that our ecclesiology is informed primarily by Scripture. And then, with Christ at the center, both our ecclesiology and missiology can shape each other.

3 comments:

Stetzer is too simple in his idea that all three somehow come directly from Scripture. Nothing comes directly from Scripture, it is always read within the context of a given society, language, and, for us, a given church.

I would say that Christology leads into Ecclesiology, and that there are certain ecclesiological realities which you can not tinker with, such as water baptism being the rite of initiation into the church, or the concept that in some way all disciples of Christ are interconnected. With some of the things you hear at Common Ground (well, I've heard them there) these key doctrines are discarded.

I still think the best theory for balancing universality and locality in the creation of contextual theologies (and thus contextual churches) is in Schreiter's 1985 'Creating Local Theologies'.

AD, Stetzer didn't say they come directly from Scripture. He said, "My point is that scripture sets the agenda and provides direction for all three- one does not come from the other but they are all derived from scripture, interact with each other, etc."

Then I would agree with Stetzer. I think when we are speaking of how new, local churches develop (with theology, liturgy and all) we are looking at a continuing conversation which involves three factors: Scripture (which does not include only the bible but other Christian texts), Local Culture, and the ethos of the missionary. So I would say there is a sort of ongoing process going on. It can lead to bad syncretism, but the process can be kept honest and fruitful by taking into account two important correcting factors: the voice of other churches today (catholicity)and the voice of other churches from the past (tradition).

Post a Comment